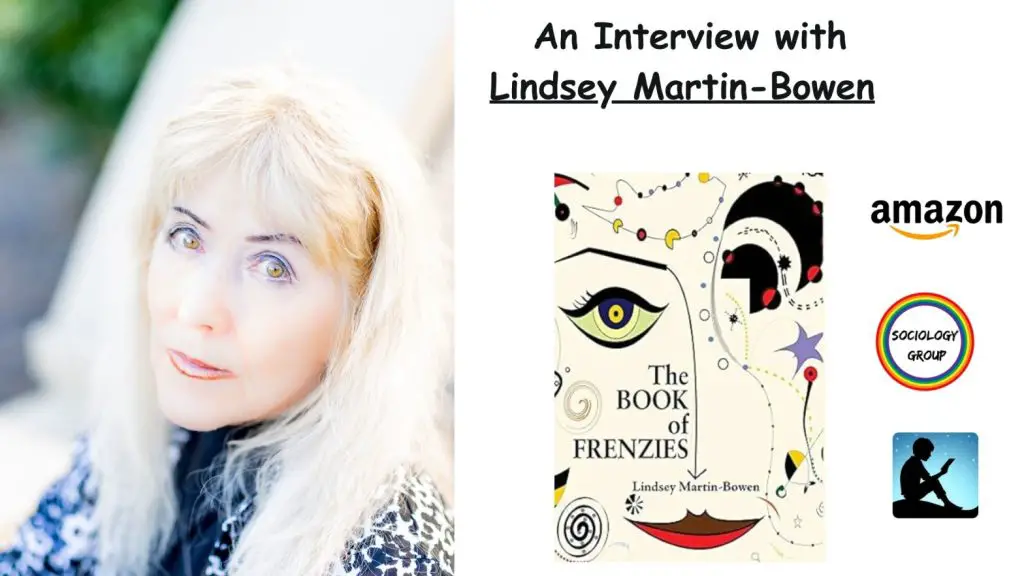

Short Bio: Lindsey Martin-Bowen teaches Criminal Law and Procedure (online) at Blue Mountain Community College in Pendleton, Oregon from January 2019 through June 2022. Until August 2018, she taught writing, literature, and Criminal Law at MCC-Longview and taught literature and writing at the University of Missouri-Kansas City 18 years. The BOOK of FRENZIES is her newest collection containing the zany poems she’s deemed “frenzies.” ( Her newest work: redbatbooks.com/checks )

1. If you had to describe your writing style or philosophy in a few words, what would they be?

That depends so much upon the specific style I am using. As a poet, I write in several voices. Usually, they are “straight forward,” but my “surreal” voice, which I employ throughout my “frenzies” (a name I borrowed from Willy Shakespeare for the zany styled poems that fill my fifth poetry collection) is almost frantic—a quite fast-paced one—and a bit “smart aleck.”

In other poems, however, I linger more upon vowel sounds. Nevertheless, my overall philosophy is that the world remains quite surreal—rarely what the media attempts to present to us, And a person’s worlds can flip “upside down” within a moment. (I will detail that more when I discuss the structure of the two collections, Inside Virgil’s Garage and Where Water Meets the Rock.

2. You have a unique background in teaching criminal law and writing. How has your experience in these fields influenced your writing and your approach to poetry and fiction.

In short, I started writing short stories and (terrible, maudlin) poetry as a child—long before I even considered studying law and teaching criminal law. If studying the law influenced my creative writing at all, it worked well for my fiction-writing. But it was harmful for my poetry. Please also see my reply to No. 3.

3. You transitioned from a career in journalism and law to teaching and creative writing. What prompted this shift, and how has it influenced your outlook on life and your writing?

My life choices likely do not align with those of many persons who decide to endeavor into “creative avocations” after they’ve reaped fortunes in business or scientific careers, but here’s how it happened:

As I mentioned in No. 2, I began seeking the creative-spiritually driven vocations when I was a child.Before I entered kindergarten, every day I would draw at a table my parents had set up in a side room near our kitchen. Even though I was very young, I was intent on creating representational art. (If fact, I recall one evening, before dinner, I created a very realistic drawing of a brown chicken.(At that time, I used crayons to color my creations.) The drawing wasn’t cartoon-like but emulated a real chicken. I showed it to my father, who was as impressed as I was.

Then later, when I tried to sketch another such chicken, I could not. I became furious—even angry with God. And suddenly, I hated my hands because they wouldn’t work right. Somehow, my father was able to console me until I settled down a bit—perhaps because he also suffered with perfectionism and a temper.J

At any rate, as I aged through elementary school, I became known as “the artist.” Neighbor women would pay me to paint their husbands or children (in oils) or in pastel chalk drawings. During these years, too, I’d create books (that I housed in portfolios containing metal clips we could punch through pages) for which I wrote significant texts along with my illustrations. Some were school assignments, such as My Trip to Canadaand one about Medieval England. Yet others were stories about Smokey the Cat (my gray feline) written in the point-of-view of the cat, and each year (for about three years), I created a Christmas book containing short stories I wrote along with Christmas stories I would copy from Readers Digest. (I always gave the authors credit for them.)

And during the 1963 Beatles “invasion,” my father brought home photos of the quartet. I rendered 8” by 10” drawings of the foursome—and individual drawings of each one. This paid well for a 12 to 13-year-old. Oodles of girls and even a few boys at my school paid me for these drawings. Unfortunately, the etchings were so popular that my weekends filled with me sketching those Beatles to sell to classmates. Other than homework, I had no time for anything else. Thus, my father assumed I’d likely become a commercial artist after I completed college.

But I had other ideas I shared with no one. After reading Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice when I was either 11 or 12, I decided, “That’s what I want to do when I grow up. I want to write books—novels.”

I told no one about this decision. Nevertheless, I started a number of stories in portfolio journals. Later, although I entered the University of Missouri as an art and theater major, in my sophomore year when students were required to take 300-level electives in disciplines other than their majors, I enrolled in literature and creative writing classes.

My experience with those studied convinced me to change my major to what I loved: literature and creative writing.

Yet after I graduated (with a BA in English Language and Literature), no jobs were offered in such a discipline. Thus, after I married, then had a child, and moved with my husband to Denver, I worked for the federal government, at first, for the National Park Service in Denver as a secretary, then convinced my husband we had to move to Washington DC, where federal agencies offered females more opportunities.

In less than a year after relocating there, the Office of Hearings & Appeals, immediately under the Secretary of the Interior, hired me as a legal editor. This is when I first considered the idea of attending law school. But I didn’t do that until many years later. After leaving Washington, DC, The Louisville Times in Louisville, Colorado, hired me as a full-time reporter/photographer. From there, I returned to my hometown, Kansas City, where I worked full-time as a reporter, section-editor, and sometime photographer for The SUN Newspapers, in Overland Park. From there, I went to be an Assistant Editor for a national trade magazine, Modern Jeweler. There, I became discouraged when I was coerced to “slant” statistics for a feature I wrote. Thus, I decided to return to graduate school and focus upon writing fiction, where I could “tell lies that reveal the Truth.”

In graduate school, I became hooked upon teaching writing and literature, and

would not have considered law school except

—within four years, my daughter would enter college, and as a single parent, my teaching gigs wouldn’t cover tuition, and

—even though I’d re-entered graduate school and was working toward a Ph.D., a number of blockages (requiring far more time) had occurred that made me question if I could ever acquire that degree. Friends encouraged me to attend law school. “You’ll make so much more money for your education.”

Thus, I took the LSAT, requested recommendations, wrote a quite creative application letter, and the UMKC School of Law admitted me. In short, my trail was quite the opposite of what you anticipated.

4. What kind of experience do you hope readers will have when they delve into The BOOK of FRENZIES? Is there a particular message or feeling you want them to take away from your poems?

Along with sharing my vision of a surreal world, which I mentioned earlier, I hope that the FRENZIES will evoke chuckles at our society’s zaniness, which often sends many of us into frenzied situations. Mainly I want them to laugh at our world’s zaniness, especially after having lost so much in that two-year COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Your book, The BOOK of FRENZIES, is described as “inventing a universe of whimsical revelations” and is said to “echo the spirits of Kenneth Patchen and Kevin Koch.” Is there a particular message or feeling you want them to take away from your poems?

Although I didn’t specifically have Kenneth Patchen or Kevin Koch on my mind when I wrote the Frenzies—many of which merely popped into my brains (even though I edited them later), I am certain those two surreal poets opened my mind into viewing this culture as surreal—and funny. I read Patchen’s and Koch’s poetry mainly when I was an undergraduate, and while they were “turning me on” to bizarre imagery with words, Salvador Dali also influenced my artwork, which became surreal. (The best landscapes I paint always have a surreal vision in them.) Surrealist imagery, whether in words or visual scenes, transforms straight narrative into art.

Later, such poets as Russell Edson and Zbigniew Herbert, influenced my surreal poetry. Yet many, many poets worldwide write surrealist poems. Last year, I was thrilled when Jonas Zdanys included my Frenzy, “Swimming in Turkey Gravy” in his .Contemporary Surrealist and Magical Realist Poetry. An International Anthology. That collection comprises 272 poets (more than 300 poems), and Dr. Zdanys wrote that he had to reject many of the more than 1,000 poems he received. And in his introduction, he explained why surrealism raises lived experience into art. In fact, he wrote that this awareness spurred him to compile this collection,

because so much contemporary poetry, especially in the United

States, seems not to understand, or at least bother with, the idea of

artifice or the gesture toward the possible. Instead, it substitutes

the epiphanies manifest through an imaginative presentation of

the world with static recordings of its familiar details. The

contemporary poetic landscape is defined by a dominant focus:

that is, it seeks to tell us, endlessly, about what writers have

experienced and to do so quite narrowly in a self-absorbed

preoccupation with the self.*

It’s interesting:My surreal poems, the Frenzies, began popping into my head when my father was dying. The Frenzies were a non-self-absorbed way to deal with death of a loved one, especially a parent, but also another close relative or a friend who has been a part of one’s life for most of one’s life, remains very surreal to me. I mean, death changes my reality immensely. (I detest death; I truly do. It causes so much pain—not solely physical—but emotional pain—by stealing persons from their loved ones. (And even if we agree with the scripture, “Death where is thy sting?” because of a belief in Resurrection, the separation, nevertheless, remains painful.)

Of course, we must adjust. Yet please note, the collection’s few Frenzies that center around death don’t evoke laughter—yet they remain “surreal” or other-worldly.

They remain art—metaphors, or in Zdanys’ words, a surreal poem (or a Frenzy) is a “metaphoric transformation,”*

*Zdanys, Jonas, “The Lyric Imagination,” an introduction to ContemporarySurrealist and Magical Realist Poetry. An International Anthology. Lamar University Literary Press (2022). pp.15-16.

6. Humor seems to be an integral part of your poetic style. What role does humor play in your work, and how do you navigate the fine line between humor and serious themes in your poems?

I’m not certain I always “navigate” that “fine line,” but hey! I’ll keep trying. J

7. Your poems are described as “painting pictures.” How do you approach visual imagery in your poetry, and how do you aim to evoke emotional responses from your readers through these images?

Perhaps visual imagery comes to me first because I started as a visual artist. I’d like to return to paint, partially because I see so many other “visions” in say, a tree. Last winter, a heavy windstorm lopped off the top of one the trees in our front yard. I’m glad that I took photos of it.

Why? Before it lost part of its top, I saw two lovers within the bark, and the huge top of the trunk also looked akin to a huge god-like head. I can still spot those items in the photo to enable me to eventually add it to the painting.

Along with visual imagery, I incorporate the other senses, especially sound and smells. I read every sentence—every phrase—aloud before I consider a poem—or a piece of fiction—complete. Many times I’ll tweak and re-tweak a poem—or a sentence or paragraph of fiction until it FLOWS correctly. Sounds often evoke as much—and often more—emotional responses in readers.

(Note. Your Number 8 repeated the question. So I’m moving on to the next one:

9. Can you tell us more about the overarching themes and inspirations behind your poetry collection, Where Water Meets the Rock, particularly the three sections, “Erosion,” “Frenzies,” and “On the Shore”?

Much like the sections of Inside Virgil’s Garage, the sections represent a process of overcoming “great pain” or “loss.” In each book, the first section contains poems about loss (or “Erosion,”) the second comprises “Frenzies,” which illustrates how we often become “zany,” “batty,” or run rampantly crazy for awhile after a great loss. We spin in circles until we collapse—then we begin rebuilding our lives with a new reality. (Perhaps that reality might even be a more surreal one—one farther from the pain.)

Although both books include allusions to ancient Greek personae, they may play more significant roles in Where Water Meets the Rock. In her review of the book for Emporia State University’s literary magazine, Flint Hills Review(2018), Camille Abdel-Jawad wrote, “Martin-Bowen’s fourth collection is divided into three parts, which fully explore the reverberating effects of loss and healing, with imagery of the sea that extends throughout the entire collection.”

She continued to explore how the collection “highlights growth, change, and the role of women” with the Greek personae in the first section: “The collection opens with “Pasiphaё Regrets (Wife of Minos II), where the persona laments: “A part of me want to dive in, /sink to the bottom, a stone, cold/and heartless—an eternity alone,/lured by the beauty of a beast/whose white belly undid me.” ** Abdel-Jawad continued to analyze the “passive” language in several of the female personae and what that indicates about women’s role in society since antiquity. althoughInside Virgil’s Garage includes a rape and some other indications of the female’s passive role, the collection does not explore that idea as deeply.

Along with the Greek allusions, Abdel-Jawad perceivedWhere Water Meetsthe Rockcontains an abundance of water, and specifically, sea imagery. Although water imagery and rhythms often appear in my poems, this collection (beginning with its title), focuses upon liquid imagery more than doesInside Virgil’s Garage.

*Abdel-Jawad, Camille. “Review of Martin-Bowen’s Where Water Meets theRock.” Flint Hills Review, Emporia State University, Issue 23. 2018. pp.138-139.

10. Can you give us an overview of your book,Inside Virgil’s Garage, and the central themes or ideas you explore in it?

Although the poems Inside Virgil’s Garage comprises vary from those in Where Water Meets the Rock, the themes remain similar. The three sections of this book are “Absurdia,” “Frenzies,” and “Other Insanities.”

“In Front of Virgil’s Garage,” the opening poem, remains the overriding metaphor for the book. “Virgil’s Garage” is a metaphor for the poet’s mind—and how it rebuilds itself after a great loss—through the zany realization that all is “vanity,” “nothing is real,” i.e. Frenzies are the reality, and then, the rebuilding begins, when the wounded poets/persons see—and accept—other insanities in our culture, including death—and rebuild their lives despite their losses.

Note, too, many scenes in Virgil’s Garage areset in “Absurdia,” my rendition of Suburbia, a culture I view as more surreal than those within a city or a town where humans seem to be more “connected” to each other. This section concludes with “Snapshots of Breckenridge,” a nine-page poem, divided into short poems, each with different names—so it doesn’t appear to be a long poem. (Even if Breckenridge is a mountain town, especially now, with the ski culture’s steady invasion, it has become a suburb, too, with its emphasis on skiing, ski clothing styles and equipment—all of which align with standard suburban values.)

Further, although a number of poems withinInside Virgil’s Garageexplore water imagery, as many focus on rock (mountain, foothills, and other earth) images, along with air and sunlight descriptions.

11. Many of your works have unique and thought-provoking titles, like CROSSING KANSAS with Jim Morrison. What role do titles play in your creative process, and how do you come up with them?

I’m uncertain how to answer this because sometimes titles come to me before the poems form. For example, the title you mentioned came to me with an idea of a persona driving her car across Kansas plains when Jim Morrison “sings from the dash,” then flows out of the stereo and perches in the front passenger’s seat, without missing a beat. (Note that the actual poem doesn’t include all of this, but this image originally popped into my brain.) The “wings of bugs/fried by the sun become yellow/triangles, pictures in sand etching/short lives that fade into dust” actually did occur. (And note that the sand paintings which etched “short lives that fade into dust” also describe the fate of Morrison and many rock singers and musicians. But I wasn’t conscious of that meaning until after I wrote it.)

So I got this title and the main image, which I tampered with for two years before I worded it so it worked. Then, the universe helped me. How?

First, for years I was a member of The Writers Place, a Kansas City center for poetry and fiction readings, classes, and so forth. In early 2015, a Writers Place member sent me an invitation to join the Facebook group, 365 Poems in 365 Days, started by another Writers Place member, James Benger. The first month, I wrote daily and unloaded numerous poems that I’d envisioned or for which I jotted notes in my journal. And once again, I started reworking the title poem, “Crossing Kansas with Jim Morrison.” Finally, after a zillion more drafts, I “got it right.”

Then, something truly amazing happened: Other Jim Morrison poems began flowing out of me. Almost all of my daily poems for the 365 were Jim Morrison poems.

In the interim, I read the book Women Who Run with the Wolves and was intrigued by the legend of “The Wolf Woman” (from both American Indian and Hispanic cultures). She became a central figure in my Jim Morrison poetry narrative that had started madly unfolding.

Within about three months or so, I’d completed a chapbook, which, on a lark, I submitted to the QuillsEdge Press Chapbook Contest. It didn’t win—but it was a finalist.

Because more Jim Morrison poems kept coming to me, within another month or so, I’d completed a short collection of between 50 and 60 poems, enough for a book.

Because it had placed in the contest—and two literary magazines had published poems from it, I thought a publisher I knew might take it. He did.

In this situation, then, the title helped me create the book, but usually, after I’ve written around 100 poems or so, I start considering which ones “rub” well against each other. Then, I usually divide them into three sections, each of which seem to fit together more strongly. Often, a title from one of the poems in a collection—or one similar, such as Inside Virgil’s Garage, based upon the poem, “In Front of Virgil’s Garage” appears to work as a poem.

I admit, though, my method of choosing titles is more madness than scientific: It appears to be based upon intuition more than diligent analysis. Often titles don’t come to me until a collection is completed—or nearly so. Sometimes I change them a time or two when a “catchier” title appears.

13. Do you have other writers in the family and friends?

As I mentioned previously, I was a member of The Writer Place and also The Riverfront Readings group, both of which comprised many writers, especially poets, with whom I became friends. I miss them terribly, but I ZOOM into readings whenever I can.

When I lived in Kansas City, my main social life was attending reading, giving reading, and the last few years in Kansas City, I set up the book sales table for writers reading that evening at The Writers Place. I find the next best experience to selling my books is selling books written by writer friends. Thus, most—though not all—of my long-term friends are poets, including a friend who now lives in New York. We became friends as undergraduates (I was a college sophomore, he a year ahead of me). And that was 50 years ago.

Family: No siblings write. They work as physicians, a nurse, a pharmacist, and engineers. One of my uncles told me he wrote poetry. But he was a “closet” poet who earned a living as a lawyer. I’ve had two cousins who worked as full-time journalists, but I don’t know if they write poetry.

14. With your experience, what advice would you give to aspiring writers pursuing a writing career while juggling other responsibilities?

If a writer hasn’t already done so, I suggest studying writing at the university or college level. Take a course from someone who’s earned at least an MA in writing. Why? Not only has this person studied writing in depth, he or she has studied literature in depth. And if an aspiring writer hasn’t read books, books, and more books by professional writers, he or she will fare better by doing so.

If the writer has studied writing poetry or fiction in-depth at the university level, I urge that writer to find organizations comparable to The Writers Place or Riverfront Readings in Kansas City. Many cities now offer Writers Places. In fact, numerous cities, such as San Francisco, have Poet Laureates for their cities—not solely in the states.

15. Last—what’s next for you as an author? Do you have upcoming projects or themesyou’re excited about to explore in future writing?

At present, I foresee only one more poetry collection, but who knows? I’m uncertain of the exact theme, but I’ve drafted a number of poems about female saints (whom I’ve researched). I’d like readers to view those saints as human beings—not the proverbial “plaster saints.” But I’m uncertain of the “theme.” That will arrive much later.

I may also revise the three novels I’ve drafted. I’ve also written a very, very rough draft of a novel that will be interspersed with poetry. Perhaps it may turn out like my first published fictional book, the novella, CicadaGrove, which won the grand prize in the 1987 Barbara Storck Creative Writing Contest. Many of that book’s chapters are very short–no longer than one-page poems. Again, I don’t know the “theme” yet.

Get ready to be moved, amused, and deeply engaged by these poems that defy ordinary logic and transport you to a realm of imagination painted in words – grab your copy of “The Book of Frenzies” on Amazon now!