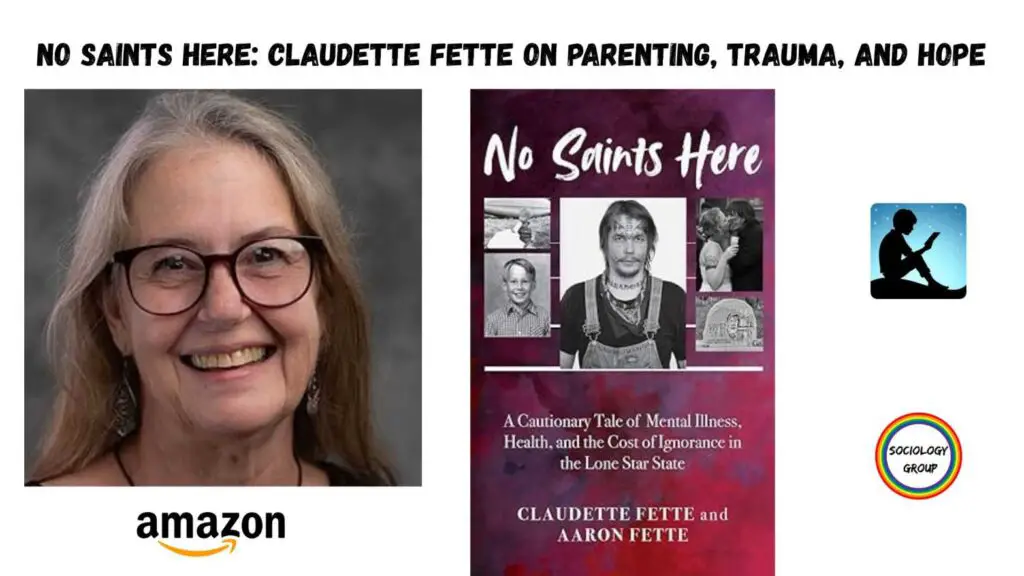

About the author: Claudette Fette is an accomplished occupational therapist, educator, and advocate. She began as a teenage mom with limited knowledge, skills, or resources, while her son Aaron, needed a much higher skill set. Still, even when he left for the streets at fifteen, after years of school failure, ineffective therapies, and an abusive treatment center, they remained close. Their book, No Saint’s Here: A Cautionary Tale of Mental Illness, Health, and the Cost of Ignorance in the Lone Star State, walks through their experiences led by Aaron’s raw and authentic voice followed by Claudette’s as his mom. Finally, she presents better alternatives in early childhood, schools, trauma, wraparound, substance use, recovery, and restorative justice that could have made a difference. After suffering through so many efforts grounded in fixing deficits in Aaron, Claudette seeks to better support youth, families, and others in her community to live lives of meaning focused instead on building what is right about them.

Today, Claudette has worked in mental health for nearly three decades across many settings including acute psychiatric hospital, homeless shelters, schools, and community advocacy. She continues to be active supporting mental health and wellbeing across the lifespan at local, state, and national levels.

- If you had to describe yourself in three words, what would they be?

Compassionate, driven, creative.

2. Claudette, when you think back to yourself as a teenage mom, what did you wish people really understood about the challenges young mothers face?

Parents just know what they know. They have the skills they learned from their upbringing, good or bad. They have whatever knowledge of trauma, infant mental health, or their own mental health that they have been able to glean in a society with pretty limited general knowledge. They don’t understand that there is more that they need. But parents need knowledge and skills, and parents whose children are exposed to adverse childhood experiences need specific supports to help build resilience.

3. You’ve seen firsthand how early childhood experiences shape a person’s mental health for life. What is one thing every community could do better to protect kids from trauma?

If I have to choose one thing, it would be to create a system to enable visiting mentors for new parents with deep knowledge of child development, effective discipline, and positive mental health promotion. Then lean into supporting families. Screen for needs and address those in the context of a supportive relationship. Programs could provide training for skills in bonding and attachment, infant mental health, social-emotional learning and self-regulation, parental self-care and mental health promotion, healthy relationships, effective discipline and more.

4. In your new book No Saints Here, you share both Aaron’s story and your own. Why did you feel it was so important to combine your experiences with evidence-based solutions?

Aaron’s experience is central and he wanted to illustrate the importance of meeting the needs of children and youth effectively, and protecting them from harmful practices. Our hope is to share the lessons we have learned and prevent our experience for another family. As a parent, I wanted to share an honest self-appraisal for a number of reasons. First, I wanted families to recognize themselves and realize we do the best we can until we know better as an antidote to the shame many of us carry. Second, I wanted to share both of our experiences to emphasize the importance of having more effective alternatives – there are consequences to failing children and families. Third, I wanted to provide the solutions that we would have benefitted from across Aaron’s lifespan, for youth and families, but also for helpers and policy makers. We must do better.

5. You write very honestly about your own mistakes and lessons as a parent. What do you hope other parents will take away from your honesty in No Saints Here?

That we do the best we can until we know better. Shame is debilitating and really serves no purpose. We have to be laser focused on effective strategies. I have plenty of regret, but that is only useful if I can use it to make something better. I hope that families who recognize themselves can let go of shame, and that others can hold some compassion for the difficult choices that families like mine make.

6. Many families feel lost in the mental health system. What’s the first piece of advice you’d give parents who don’t know where to turn?

Find a knowledgeable family-to -family organization. These are families who have been where you are and who understand the systems you need to navigate. Ideally, they also have a broad understanding of best practices and can help you advocate for what you need. Read up on strength-based practices, wraparound; multi-tiered systems of support, social and emotional learning, and restorative circles in schools; and look for coalitions advocating for these – you can crash most of them and learn from leaders in their fields.

7. No Saints Here talks about evidence-based practices — like wraparound care and trauma-informed schools. What’s one approach you wish every school or community would adopt today?

It is hard to limit this to one practice, but as an overarching principle I think strength-based practice. This means not only looking for what children and youth (and their families) do well, but also creating regular opportunities for them to exercise their strengths. It means being creative and exploring ways those strengths can be used to decrease deficits. Everyone needs space to experience themselves as competent.

8. You became an occupational therapist and professor because you wanted to make a difference. In your experience, what’s the biggest barrier that keeps good mental health ideas from becoming everyday practice?

Resources. Funding for skilled supports such as knowledgeable family-to-family support systems and robust multidisciplinary mental health teams; and for dissemination of best practices with fidelity.

9. You’ve worked in hospitals, homeless shelters, schools, and community programs. Where have you seen the most hope and progress?

The potential for recovery is best the earlier we can intervene. Because school districts vary broadly, this is not every district, but many districts have embraced trauma sensitive schools, multitiered systems of support, and mental health promotion. As a school based occupational therapist, I was permitted to lean into providing support for students and teachers early rather than waiting for them to fail. This looked like the teacher being able to call me in for any situation or child she needed help with. This could be classroom strategies to help maximize attention during reading, attending to a student that the teacher had concerns about either through providing accommodations in the classroom or whatever supports they needed to enable successful participation. I supported children in the least restrictive environment which meant I did not pull them out of class unless absolutely necessary, rather embedded support in their classroom, often benefiting multiple students. I might provide support to teachers to facilitate activities building all kinds of skills including communication, emotional intelligence, and positive mental health promotion, or on occasion I also facilitated activity based mental health groups after school, again providing early supports for children without needing to label them at all.

10. You’ve connected with many other family advocates over the years. What gives you hope when you look at the next generation of parents and professionals?

There are some structures to support family advocates, again often woefully under resourced. It is important to assure that family advocates have access to evidence-based practices and the most current strategies so that they can both come back home and help their systems live up to expectations, and so they can assure youth and families have access to what they need. Professional conferences are much more open to including families than they once were.

11. Some people see terms like restorative justice or trauma-informed care as just buzzwords. How would you explain, in plain words, why these really matter for families and communities?

Restorative circles in schools are about teaching children effective ways to resolve conflicts and to take responsibility when they have harmed someone else. When they do make mistakes, the process also provides them a path back to being a respected member of the classroom. It gives voice to the person who was harmed. For adolescents and adults in the justice system, restorative justice also creates a mechanism for them to take responsibility for harm they have done. Here it also gives power and voice back to people who were harmed. They have the opportunity to tell the person how their actions impacted them. The process tries to meet the needs of both victim and offender. This is instead of our current system in which the victim is represented by the prosecutor and the offender by another attorney, but the people at the heart of the offense have no roles. In the system we have, cases often don’t even go to trial; the district attorney escalates the charges to the most damaging they can get away with and then uses those inflated sentences to bully the offender into a plea bargain. By the time it is all said and done, the offender is several steps removed from their wrongdoing and have likely learned nothing of any value from the experience. If our goal is to bring people back to society, we need to take the opportunity to help them build empathy and increased motivation to do no harm going forward.

Trauma informed care is really about accurately understanding what you see as someone who provides care. If you don’t understand trauma responses, you are likely to misinterpret them and respond in ways that are inappropriate and often make things worse. Once you understand trauma and what trauma responses look like, you cannot unsee them. Then it is just about learning how your reactions might impact the situation and what you need to do differently.

12. When readers finish No Saints Here, what’s one small action you’d love them to take right away?

That will vary based on the reader. My hope is that whatever their reason for reading, they look for the thing they can apply to the needs most important to them. They might look for opportunities to warn families about the Troubled Teen Industry (TTI). They might reflect on people around them who may have experienced trauma and reflect on their experience of the systems they interact with. They might dive into strengths-based practices, assessing their own strengths and those of a child, youth or young adult they care about, and then think about how to create opportunities for them to use those strengths. They might look at youth, families, and/or unhoused people in their communities who are struggling with more compassion. They might talk to a teacher in their community and ask what kinds of support they are able to access. They might take the principles of wraparound and/or recovery and use them to evaluate mental health supports in their community. Again, I hope they identify something that they care about and evaluate how that person, group, or system are doing.

13. After everything you’ve lived, worked for, and written, what keeps you motivated to keep teaching and speaking up for change?

Aaron and all of the people I have worked with who have parallel stories. They deserve better.

14. Do you have other writers in the family or among your friends?

I come from a long line of storytellers and artists but few published. The exception is my brother-in-law, Bernie Fette, who wrote Men Don’t Tell several years ago. It is a memoir of his experience as a survivor of spousal abuse. Academicians write so I work with many writers, although our writing may be a bit harder to read. With this book I hope to bridge the gap between scholarly writing and an easier to digest genre to attempt to make evidence-based practice a bit more accessible. I do work with a number of people with lived experience who are writers, chronicling their feelings and experiences in narrative.

15. If someone wanted to reach out to you for a project or collaboration, what’s the best way for them to get in touch?

Either email cfette@twu.edu or my blog at https://aaron-voices.com/moms-blog I am hoping to create an interactive space … perhaps a blog on YouTube?

16. Why do you think we still treat mental illness so differently than physical illness — even though the consequences can be just as deadly?

I think the stigma of mental illness is tied to the need to “other” what we are afraid of. And we are very afraid of mental illness. If one can distance themself enough, there is a false sense of security. I also see us do this with other chronic illnesses – cancer, autoimmune disorders, and others. I see us blame people for exposure to toxins, levels of stress, etc. in illnesses, whether physical or mental, that we fear. It gives a sense of control if we can define the risk factors in ways that exclude ourselves. Mental and physical health are also interwoven in the many correlations across illnesses – physical and mental. That said, knowledge is power and mental health is really just another part of the human condition. Many of us will have the opportunity to become resilient as we cope with all sorts of illnesses.

17. There’s a lot of talk about “resilience,” but what do you wish people understood about how dangerous it is to expect people to just ‘bounce back’ from trauma on their own?

No one can claim to be resilient without experiencing adversity. Bouncing back may not the best expectation to hold. The reality is that trauma is common and it has multiple trajectories. Some people exposed to the same situation do not appear to be impacted whereas others experience it as traumatic. This has to do with prior exposures to trauma as well as coping styles. Some of those people who don’t respond may cope by disassociating and move forward by not dealing with it. That doesn’t mean it has no impact. It also doesn’t mean that we can force a particular response based on our expectations. I think perhaps the most important thing is to respect individual autonomy in response to trauma.

We need to recognize trauma responses, acknowledge those with respect, and reflect on what resources an individual needs and ideally who might best provide those. Sometimes the best thing I can do is to understand what I am seeing and make sure that others in the environment also understand so that we all respond appropriately. Therapy around trauma requires trust and relationship and if I do not have the capacity to be there over time, the best I may offer is to resist retraumatizing and create a supportive environment.

There are evidence-based practices related to trauma across the lifespan. Trust Based Relational Intervention (TBRI), Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) are several that require advanced training. Bessel Van Derr Kolk and Bruce Perry offer overarching insights – 1. Create safety, listen, give control, activity is helpful, 2. Build relationship, 3. Help with self-regulation, building healthy routines & relationships.

18. What do you think the biggest myth is about families who have a child with serious mental illness — something no one wants to admit out loud?

I don’t know that they are afraid to admit it sadly, but the biggest myth is the idea that we should just punish them until we force them to behave. Punishment is not effective discipline, particularly for children, youth, adults with serious mental illness. Discipline is teaching the behaviors that you would like to see. Mistakes are part of learning.

19. From your experience, what’s one thing our justice system needs to face honestly if we really want to break the cycle for people with mental illness and addiction?

Prison creates more trauma for people who have already experienced too much adversity. Prison culture sees its primary mission and public safety and prisoners as a threat to it. That mindset is absolutely backward from the one needed to build recovery. Instead, it would be more effective to look at needs and restorative practices.

20. What’s one hard truth about our culture’s view of homelessness that you hope No Saints Here makes impossible to ignore?

People who are unhoused are human beings.

No Saints Here: A Cautionary Tale of Mental Illness, Health, and the Cost of Ignorance shares the powerful journey of a mother and son navigating trauma, resilience, and broken systems. Honest and thought-provoking, it sheds light on the urgent need for compassion and reform in mental health. Available now on Amazon.

We believe in sharing knowledge with everyone and making a positive change in society through our work and contributions. If you are interested in joining us, please check our ‘About’ page for more information