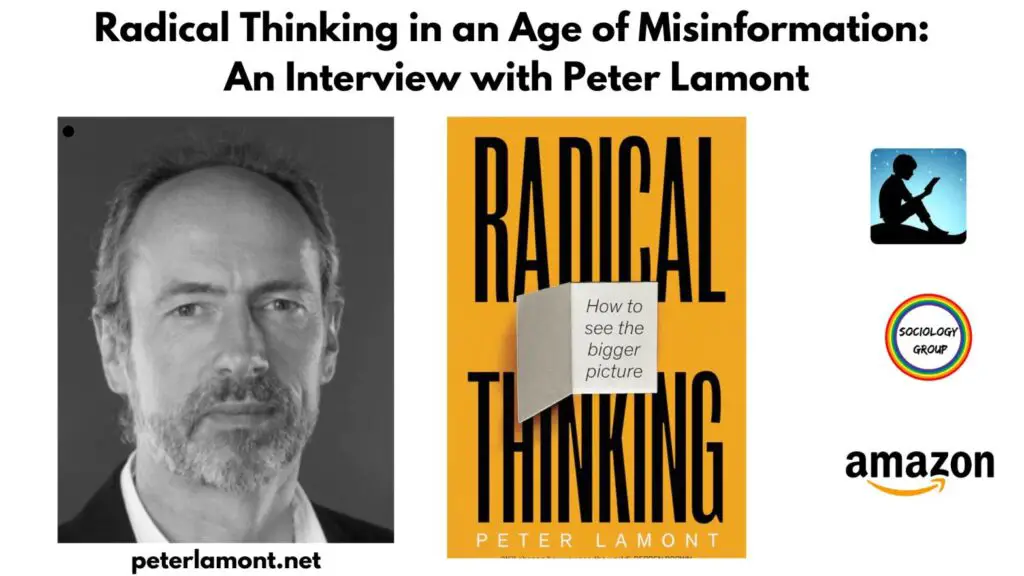

Peter Lamont is a Professor of History and Theory of Psychology at the University of Edinburgh, and a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. His previous five books, and many articles, have been on a variety of curious topics, such as magic, belief, wonder and critical thinking. He is also a former professional magician and has been a consultant and contributor to many television and radio programmes. His popular books have been highly praised in the popular press, and by individuals such as Derren Brown, Teller (of Penn and Teller), Simon Singh and Hilary Mantel.

1. Could you briefly introduce yourself and share what initially inspired your interest in the intersection of magic, psychology, and history?

I’m Professor of History and Theory of Psychology at the University of Edinburgh. Before I became an academic, I worked as a magician. So, though I’m a historian, I ended up in a Psychology department because my first job was doing research on the psychology of magic. Since then, I’ve studied the history and psychology of magic and the paranormal, and related topics such as belief and critical thinking.

2. If you had to describe yourself in three words, what would they be?

Ask. Someone. Else.

3. Are there other writers within your family or social circle who have influenced your approach to writing or thinking?

I’m the first academic from my family, so my influences have come from books written by strangers.

4. Was there a pivotal moment that led you to write Radical Thinking?

It began as a critical thinking course, which I first taught in 2019. It was designed to be taught in-person so, when COVID happened, I couldn’t teach it. That’s when I began to write the book that became Radical Thinking.

5. Which authors or thinkers have had a significant influence on your intellectual development?

I’ve drawn on the work of many different folk, including Michael Billig, David Bloor, Kurt Danziger, Michel Foucault, Erving Goffmann, Ian Hacking, Jonathan Potter, Graham Richards and Roger Smith.

6. Your book Radical Thinking challenges readers to examine how they perceive the world. Why do you feel this message is especially urgent today?

The central point of the book is that, whatever our personal worldview might be, it’s limited by things that we can’t see. We can’t see them because they’re in the ways that we look at the world. So, if we wish to see the bigger picture beyond our own limited view, we need to understand alternative views. I think this matters more than ever. After all, we now have access to more information than at any time in history, yet our views appear to be narrowing. We struggle to understand people who disagree with us, and we’re increasingly polarized. That’s why we need some ‘radical thinking’.

7.Your work bridges magic and psychology. How does performance magic help us understand the limits and mechanics of human perception?

Everything that you think – about any subject at all – is based on what you notice. Unless you notice something, then it won’t cross your mind. However, we notice a fraction of what’s going on. So, our worldview is always limited. Magic is a perfect example of this. The magician directs your attention so that you notice some things, but miss other things. For example, you see a ball in the magician’s hand and, a moment later, you see that it’s gone, but you fail to notice that it went up the sleeve.

8. Can you share an example where a magic performance clarified a complex psychological concept for your audience or students?

Let’s take the example above. I hold up a small ball in my left hand and I tell the audience that it’s going to disappear. I then hold up a different ball in my right hand. At that point, they look at the second ball. A moment later, when they look back at the first ball, it’s gone. So, rather than simply being told that we notice a fraction of what’s going on, they experience this for themselves.

9.You’ve explored how individuals can perceive the same situation in entirely different ways. What does this suggest about how we assess truth in an age of social media and information overload?

Everything that we think is based not only on what we notice, but also on how we interpret it. And, whatever it is, we can interpret it in different ways. So people notice different things and interpret them in different ways. This is the case with all things, including whatever we see and hear on social media. The problem arises when we forget that we notice a fraction of what’s going on, and when we think that our interpretation (of the things that we notice) is the Truth. None of this is new. However, social media is driven by the desire for attention, which encourages exaggeration and one-sidedness.

10. In your view, how do unconscious assumptions shape our understanding of reality—and how might people become more aware of them?

Unconscious assumptions are unavoidable. Right now, for example, you’re assuming that I wrote this. In daily life, we need to make assumptions – that the world tomorrow will be much the same as it is today, that things will be where we left them, that the buses and trains will run, and so on. We become aware of our assumptions when the unexpected happens. For example, during COVID, we soon became aware of how much we took for granted. However, if we talk to people who have different worldviews – who don’t share our assumptions – we’re reminded of the assumptions that we make.

11. What role does belief play in how people create meaning, and how can we maintain openness without falling into cynicism?

When we look at the world, we need to interpret it, and we can interpret it in different ways. Indeed, whatever evidence we encounter, we can always interpret it in a way that’s consistent with what we believe. This is the case with conspiracy theories, where even a lack of evidence can be seen as evidence of a cover-up. However, it’s broader than that. Once we take a position, we can dismiss opponents as untrustworthy and anything they say as unreliable. But we don’t need to take a position on everything. We can consider alternative views and compare them. We can understand where each is coming from, then decide which we find more convincing. And we can wonder what it would take to change our mind. The bottom line is this: thinking is a process, not an outcome. It’s a path that we take until we reach a position, but it needn’t be a final position.

12. What practices would you recommend for cultivating the kind of radical thinking your book promotes?

It begins with curiosity. Curiosity comes from an awareness that there’s something you don’t know. So, next time you hear someone express a view that makes you think: I don’t understand why on earth they would think that?, take the time to listen to them. Rather than look for reasons why they’re wrong, try to understand where they’re coming from. You don’t need to agree with them, but you can understand how they got there.

13. From your perspective as a historian of psychology, how have perceptions of belief and cognition evolved- and what misconceptions still persist?

Our views about belief and thought, and the mind in general, have changed in countless ways. The most significant shift, in recent history, has been towards the computer metaphor of the mind. The misconception that persists is that it’s not a metaphor.

14. What can past phenomena like mesmerism or spiritualism teach us about the psychology of belief today?

For the last two centuries, we’ve been having much the same argument, whether it’s about mesmerism, spiritualism, paranormal or other extraordinary beliefs. We’ve argued about the facts (did it really happen?), about the reliability of the witnesses (can they be trusted?) and about how likely such things are (are they plausible?). We’re having similar arguments today about fake news and conspiracy theories. However, these questions also apply to ordinary beliefs. The difference is that, since most people don’t hold extraordinary beliefs, believers need to work harder to justify their beliefs. This is why they’re a useful guide to how we form the beliefs that we do.

15. How do you incorporate your research themes into your teaching to encourage critical and independent thought?

I try, in everything I teach, to reflect the themes that I think are important to think in a critical way.

16. For those who wish to connect, collaborate, or learn more about your work, what’s the best way to reach you?

I have a personal website (peterlamont.net) and I recently started a substack (The Faculty of Wonder), which includes pieces of curiosity.

We believe in sharing knowledge with everyone and making a positive change in society through our work and contributions. If you are interested in joining us, please check our ‘About’ page for more information