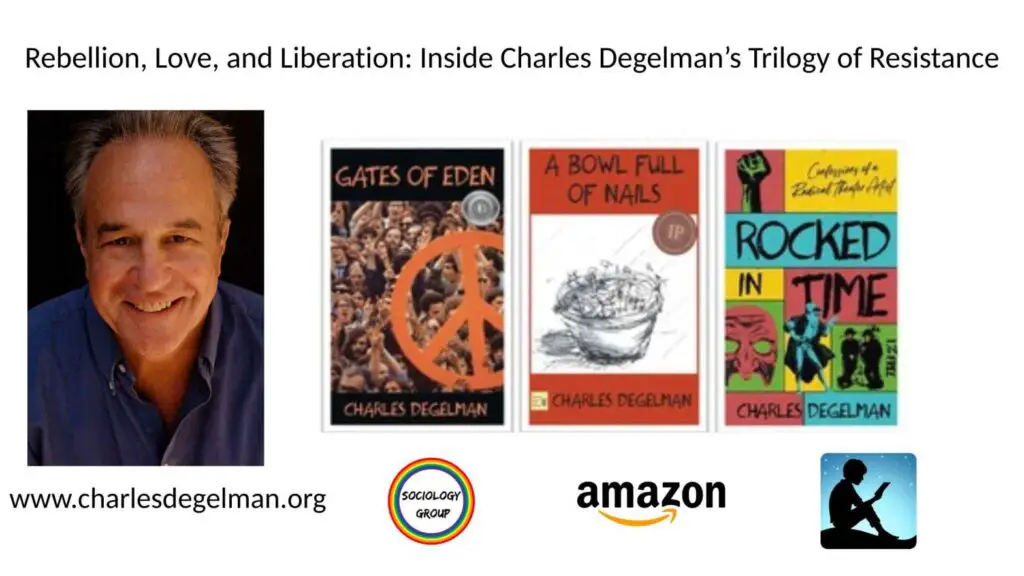

About Author: Charles Degelman is an award-winning novelist, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. A true storyteller for the resistance, he draws from his own experiences in the civil rights, antiwar, and feminist movements of the 1960s and ’70s. His Resistance Trilogy — Gates of Eden, A Bowl Full of Nails, and Rocked in Time, blends history and fiction to capture the passion, humor, and struggles of a generation that dared to challenge the system. Beyond writing, Degelman has worked as a screenwriter, documentarian, musician, and professor, always weaving art with activism. http://www.charlesdegelman.org

1. If you had to describe yourself in three words, what would they be?

Compassionate wise guy

2. Are there any authors or books that deeply influenced your writing style?

Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, Lewis Carroll, Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, J.D. Salinger, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Thomas Wolfe, John Dos Passos, John Steinbeck, Doris Lessing, Virginia Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, James Joyce, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Bertolt Brecht, D.H. Lawrence, Dorothy Parker, P.D. James, Roberto Bolano, Ernest Hemingway, John Nichols, Marcel Proust, Antoine de St Exupery, Richard Powers, Toni Morrison, Octavia Butler, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, Barbara Kingsolver, Eduardo Galeano, Pablo Neruda, Colson Whitehead, LeRoi Jones, Gabriel Garcia Marques, Olga Tokarczuk, Lauren Groff, Rachel Kushner, Jane Austen, Arundati Roy, Jhumpa Lahiri, Lawrence Durrell, Graham Greene, E.L. Doctorow, Jennifer Egan,

3. Rocked in Time completes your Resistance Trilogy. What inspired you to devote three novels to the rebellion and upheaval of the 1960s and ’70s?

Actually, the Resistance Trilogy began in a theater, as did Rocked in Time. I was working on a new play when the antiwar movement of the 1960s came up. Several actors expressed amazement that there had been a movement to stop the Vietnam War.

They also had no awareness of our movements to demand jobs and income for marginalized minorities, our efforts to foster gender equality, and our resolve to tear the roof off and expose the hypocrisy of the American Dream. One young actor responded with “wow! We just thought that all you guys did was smoke dope, get laid, and, like, drop out.”

I was aware that the success of the antiwar movement had been eroded by the Establishment. We had turned American society upside down. The power structure didn’t like our success and set out to diminish our impact on society. We had left our mark on The Great Society with its racism, misogyny and illegal, immoral wars. But the actors’ ignorance about ‘60s resistance movements reflected the long-term Establishment backlash. I was shocked by the actors’ response to the most powerful liberation movement in U.S. history. They didn’t even know it happened!

I decided to set the record straight about our impact on the war, our collaboration with the civil rights movement, and the triumphs of feminism and environmentalism. We broke the stranglehold on what was being taught at universities and what was not. I wanted to talk about all of that… and more! So, I sat down to write the Resistance Trilogy.

4. Each volume explores a different “world of resistance.” How does Rocked in Time differ in focus and mood from Gates of Eden and A Bowl Full of Nails?

Gates of Eden, Volume I of the Resistance Trilogy, follows a handful of young Americans growing up absurd in the 1950s. As they come of age, Gates’ characters become activists in the civil rights, anti-Vietnam, and feminist movements of the 1960s.

I set A Bowl Full of Nails, Volume II of the Resistance Trilogy, in an abandoned mining town high in the Colorado Rockies. Our protagonist, burnt out in the radical theater scene, flees the city to work with his hands and get his head together, only to discover that — even amid rugged mountain beauty — there’s no escaping the war at home. Nails explores the personal and political dramas that unfolded in the back-to-the-land movement, when city dwellers carried their newfound communal idealism into the wilderness.

Rocked in Time, Volume III of the Resistance Trilogy, explores a third realm, the role that art played in highlighting and commenting on the conflicts, comedies, and injustices of the period, as experienced by actors in the San Francisco radical theater scene.

5. Your trilogy doesn’t just tell stories of rebellion — it shows how rebellion transforms the rebels themselves. What hard truths did you discover about change, sacrifice, or freedom while writing these books?

I lived through the times and the realms that I wrote about in the Resistance Trilogy. Although the first volume was research-heavy in areas that I did not experience — Vietnam, the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, the struggles of movements like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), my real life had been transformed by what I fictionalized in the Trilogy.

While writing these stories, I was often reminded how exciting and terrifying those times were, how deeply our lives were changed by the consequences of our resistance, and how high the stakes ran in our efforts to stop a murderous war abroad, counter racial violence in the South, and create high-quality art that engaged, educated, and entertained while it exposed and explained the world we saw bursting into flames around us.

Ironically, our most challenging struggle came from the male-female relationships that we formed while fighting “The Man.” As we fought for equality in race and class, entitled, progressive men rose quickly into leadership roles that were quickly and righteously nixed by women who were as smart, highly competent, and often better at resistance than many of the men. The women became mad as hell. They understood that a liberation movement meant nothing until all its members were free.

Through the antiwar, civil rights, and radical arts scenes, the personal battles of men and women became political battles as urgent and powerful as any of our actions against war, racism, pollution, and mediocrity. Some men learned, some did not, but women’s liberation became — and continues to be — one of the most lasting and critical struggles of the times.

6. What were the biggest challenges in balancing historical accuracy with fiction in this final book?

Historical accuracy was not difficult while writing Rocked in Time. I was already an experienced actor, and had been instrumental in the creation and performances of a radical theater company’s productions in those years. The biggest challenge came with the creation of the novel’s characters. As with Gates of Eden, I wanted to create fictional characters who could interact with authentic historical characters. In Gates, I developed fictional characters who interacted with Bob Dylan, Presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey, black power advocate Stokely Carmichael and others. I created a special feature separate from the plot and its characters called “Masters of War,” a series of sidebars in which real historical characters provided historical context without choking Gates of Eden with exposition.

In Rocked in Time, the timeline of real events began in the rapidly growing political resistance and counterculture movements and moved forward, driven by the fictionalized characters and theater productions, a tour of rebellious campuses nationwide, and interactions with people like Black Panther Bobby Seale and Kathleen Cleaver, filmmaker Shirley Clarke, and SDS leaders like Tom Hayden and Bernadine Dohrn. I enjoyed poring over old recordings, transcripts and articles until my novel’s characters could interact believably with true historical figures.

7. Which character in Rocked in Time surprised you the most as you wrote them?

When I write, I often stumble across incidental characters who simply will not shut up. When I recognize an authentic voice coming out of a character, I pay attention to what she or he is saying. They often become vital to whatever story I’m inventing. Madeline Singer, who began as a kid hanging out in Washington Square Park, became a major player in Gates of Eden.

In Rocked in Time, a minor character named after the black poet Nikki Giovanni became a major character. She began as a minor player because I needed a black actress to diversify the fictional theater company. But Nikki was a talented actress and dancer who began to cause good trouble in the most alluring ways. She also fell reluctantly in love with Rocked in Time’s protagonist and drove the plot in directions I hadn’t been able to imagine without her.

8. Looking back on the Resistance Trilogy as a whole, what do you feel connects all three books at their core?

The spirits of resistance, rebellion, and love run strongly through all three volumes of the Resistance Trilogy. I wanted to revisit the different realms of resistance that had been diminished or lied about by the power structure that we threatened so profoundly in the 1960s and ‘70s with our political and cultural movements. I wanted to set the record straight about our impact on the Vietnam war, about the progress we made in civil rights and other elements of social justice including the triumphs of feminism and environmentalism. We also broke the stranglehold on what was being taught at universities and what was not. I wanted to talk about all of that… and more!

9. How did you want the ending of Rocked in Time to feel for readers who have followed the trilogy from the start?

I wanted an open-ended finish Rocked in Time. I hope the reader will ask what happened to our ongoing protagonists, the theater company and the people, places, and tumultuous events that characterized that time. I hope to give a sense of hope to the future, without setting the future in type. As with any historian, doctor, or scientist, I am reluctant to predict, but we can learn from the past and move forward into the present with resistance, rebellion, and love.

10. You describe yourself as a “storyteller for the resistance.” What does that mean to you today?

I’ve been around for a long time. I’ve been an observer of people, places, events, of history and political struggle since I was a teenager. I lived through McCarthyism as the son of a blacklisted scientist. I watched the Cold War gain momentum with CIA-driven regime changes, proxy wars, and nuclear proliferation. I grew up in a progressive family where we discussed the march of history and current events. I knew what was happening in the world.

As I came of age, I began to follow the paths that led toward 1960s resistance, rebellion, and love. All these events took place in response to the most egregious abuses of civil, political, and military power, all leading toward terrible suffering and social injustice. I studied history and political theory and found others in my generation who gravitated toward political art and culture, brothers and sisters who would push back at the injustices I watched develop through the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s.

In all my time as a sentient, politically, personally, and culturally aware human, I have never witnessed anything as blatant, cruel, disgusting, and wanton as the efforts of Donald Trump and his handlers to destroy democracy and human dignity in the name of money, power, and politics. Now, more than ever, writers and other artists are stepping up to use their talent, skills, imagination, and purpose to move beyond resistance to clear opposition. I feel driven to continue using my art as a tool for social change. As poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht one said, “change the world; it needs it.”

11. Rocked in Time is set in the Vietnam era. What parallels do you see between that time and the social and political climate today?

Today is worse. Even during the tumultuous Presidencies of Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, we had a functioning Congress and a centuries-old respect for the law and the Constitution. Still, we recognized the hubris, power abuse, and hypocrisy that labeled us the ugly Americans. Then, we were the radicals who wanted to change the world. We dreamt of an egalitarian society, where the government, supported by the people, supplied basic human needs — food, clothing, housing, medical care, and dignity.

Yes, Jim Crow still oppressed the South and young civil rights workers were murdered for registering black voters, but thousands upon thousands of activists demonstrated for equal protection and the Civil Rights Act was passed into law.

Yes, Lyndon Baines Johnson presided over an illegal, immoral, racist war of suppression in Vietnam, where American troops fought, killed, and died to prevent fair elections and the unification of the country whose manifesto was based on the American Declaration of Independence. Although Americans were deeply divided over the violent American presence in Vietnam, antiwar sentiment spread gradually and steadily from antiwar activists to the population at large, culminating in the defeat of American military action in Vietnam and the unification of the nation.

In the 1960s, the largest student movement in American history, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) led young people on a powerful march of activism. The Port Huron Statement, SDS’s manifesto reflects the longing for change in those times: The search for truly democratic alternatives to the present, and a commitment to social experimentation with them, is a worthy and fulfilling human enterprise.

Compare the intentions of the New Left radicals above to that of the white supremacist movement that propels the radical right wing of Project 2025: Project 2025 is a manifesto and blueprint for a radical Right Wing restructuring of American constitutional law and power, written by Trump administration officials and the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that opposes abortion and reproductive rights, LGBTQ rights, immigrants’ rights, and racial equity.

In short, the Trump administration, the Heritage Foundation, the radical Supreme Court and the power behind them want to make America white again, with a wealthy minority served by an impoverished middle-, working-, and immigrant class. These radical extremists are busy eroding the democratic institutions we have fought so hard to create and protect in America. In the words of poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht, “truly, we live in dark times.”

12. What do you think today’s movements for social change could learn from the theatrical and creative tactics of your generation?

I’m full of admiration for a new generation’s approach to today’s growing wave of social injustice and abuse of power. We had land line telephones, mimeograph machines, and mass meetings. Today’s resistance uses cell phones, email, texting, computer graphics, zoom-style remote gatherings to spread the word and strategize. Although the Internet and social media can generate plenty of garbage and pollution, it has also provided the new resistance with powerful means of communication, innovation, and a universe of information.

Because the political and economic atmosphere has grown more complex, extreme, and personally impactful, young people are watching a radical social and political invasion and coup attempt unfold around them in real time. They are using the Internet and social media to identify today’s rapid political change, analyze its causes and consequences, and develop their own strategy and tactics to resist the current attempts to frighten and oppress the population and destroy democracy.

I wrote about our resistance movements to present the spirit and letter of protest to younger generations. I wish them to be outraged and outrageous the way we were. I hope they will learn the power in numbers that characterized our movements. Although I hope they use work like my Resistance Trilogy to learn what came before, Americans seem to be developing doing their own resistance, rebellion, and love.

Fortunately, many of our generation’s activists haven’t forgotten the power of resistance, and the multigenerational character of today’s resolve to fight the power brings the best of all generations to the forums where anger, cruelty, and violence must be met by truth and the need for change.

13. You’ve worked as a screenwriter, documentarian, and professor. How have these roles influenced the way you craft historical fiction?

All my work informs itself. To know my creative origins, know that I began my artistic endeavors as an actor, and continued in the theater for many years. Frankly, I don‘t know how writers can craft dramatic scenes or even workable dialog without having acted and experienced how dramatic conflict, language, syntax, voice training, and character development to drive a story forward.

I am also a musician. I learned how to sing in church and took up playing and singing as a teenager during the folk music renaissance of the late 1950s and early 1960s. I also studied harmony and rhythm, two musical elements that appear in my narrative writing. I believe any narrative carries its own rhythm; it must rock, swing, or groove to carry the reader forward.

Teaching also figures large in my fictional craftsmanship. I’m forever grateful for the unforgiving demands my students have made that I clarify, simplify, and unfold in sequence. My screenwriting work also draws on my acting experience in the creation of terse, believable scenes.

Screenwriting also serves to clarify narrative fiction. In a film script, unless you fall back on voiceover narration which often muddies the dramatic waters, you have five elements: setting, characters, dialog, action, and, arguably, music. Anything beyond those five elements usually reveals that you are telling the story, rather than showing it. In fiction, of course, the writer “tells” and shows. Given the confusion over the overused “show, don’t tell,” mantra, I find it helpful to know when am showing and when I am telling. It’s all about narration and narrative voice. Every novel has its narrator, often not the author and often not reliable.

14. If you could see your Resistance Trilogy adapted for the screen or stage, what would you want audiences to feel as they experience it?

I’ve had my fill of terrible films and adaptions of novels set in the 1960s. Most people who climb the career ladder like Larry Kasdan “The Big Chill,” “Mississippi Burning,” or Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper in “Easy Rider” had no idea what the civil rights and antiwar resistance movements were about; they were too busy building their careers to be seriously involved in the resistance movements. Most attempts at capturing the drama of second-wave feminism have also failed.

I wouldn’t look for historical accuracy as much as I would want a film or play based on my work to capture the spirit of the times: a reasonable amount of contextual background (without being lengthy or didactic); the development of characters and dramatic exposition that revealed the passion, intelligence, ingenuity, humor, sexuality, and jeopardy generated by the activists who put their lives on the line to stop the racism, misogyny, and the military-industrial machinery that created the injustice in the beginning. Sure, there was plenty of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but I would want the audience to viscerally feel the danger, the serious nature of the resistance and its participants, and the intensity, joy, and complexity that we knew during those days that changed all of us.

15. Do you have other writers among your family and friends?

Yes. I am married to a writer. We met in the theater in San Francisco and immediately recognized our commonality. We wanted to create high-quality theater that served as an entertaining and uplifting tool for social justice. We produced original theater together for decades. I left the theater first because I had come up against the limitations of collaboration; my partner left later, when Covid and Actors Equity teamed up to make theater impossible. Today, my partner and I write fiction and have become our own best readers, editors, and enthusiastic supporters. We also have a small crew of trusty beta readers who can look at our rough work with compassion, intelligence, and experience.

I also live in Los Angeles, a city full of writers. They’re everywhere. As a professor of writing and media studies, I met many writers at university. I also value writing workshops where there are often bright, like-minded authors with whom to share my work.

I also had a mentor who meant the world to me. John Rechy, prolific novelist and essayist ran a master class that I attended for seven years. I can say confidently that I view my writing in two periods: before John Rechy and after John Rechy. Although Rechy taught me enough writing theory and practice to fill volumes, I would emphasize two rudiments that John Rechy taught me. First, fiction writers are the only honest writers. All the others — the historians, researchers, social scientists, the writers of religious tracts — are liars. They claim to be writing the truth when, in fact, they are simply shoving data through the jumbled sock drawers of their minds. Fiction writers are the only literate workers who come out and admit that they make stuff up. All fiction is a lie, and — in the words of my wordsmith wife and soulmate — “the truth lies in stories.”

16. What advice would you give to writers today who want to tackle political or historical fiction with the same courage, honesty, and rebellious spirit you bring to the Resistance Trilogy.

I wrote the resistance trilogy because I wanted to set the record straight about an often-trivialized, misunderstood, and diminished time in our nation’s history. I also wanted to capture the personal passion, resolve, intelligence, and ingenuity of my characters and the destructive nature of their antagonists. To write fiction of this kind, I advise people that — if you haven’t lived through it, or even if you are immersed in today’s critical resistance — know your subject well. Research and think critically about what you want to say with your work and give it hope and forward momentum. We stand at a critical point of inflection in the history of the world, its creatures, and of nature itself. In Bob Dylan’s words, “know your song well, before you start singin’.”

17. Now that you’ve completed this trilogy, what questions about resistance, community, or art do you still feel driven to explore in your next chapter.

In the same way that I knew I was done with a memoir when I had nothing more to say about myself, I am through with my retrospective on the 1960s. I’m 80 years old. I was born on the day before the Allied forces drove the German army out of Paris. Now, eight decades later, I am witnessing the end of a period of American hegemony on the international stage. I have lived many lives, as country boy, city man, musician, actor, writer, scholar, professor, carpenter, and utopian communard. What would such a man be thinking, feeling, recalling, regretting, anticipating?

I want to explore my age from the outside, as an unreliable narrator, who has lived through America’s long period of world hegemony, and is now looking energetically forward while he reviews his experience. The narrator will not be me, but he will be a man who has taken advantage of the entitlement of manhood and its oppressive elements. As is often the case, I have no idea how I will accomplish this next literary task, but I’m looking forward to writing it, as time keeps slipping into the future.

18. If someone wanted to reach out to you for a project or collaboration, what’s the best way for them to get in touch?

One of the best ways to reach me is via direct message (dm) on Instagram @charlesdegelman, or on Facebook direct message at Charles Degelman, Author. Interested parties can also peruse my work on LinkTree at linktr.ee/charlesdegelman

Don’t miss Charles Degelman’s powerful Resistance Trilogy. Grab your copy today on Amazon and dive into stories of rebellion, love, and change.

We believe in sharing knowledge with everyone and making a positive change in society through our work and contributions. If you are interested in joining us, please check our ‘About’ page for more information